Before dawn, I stood at the starting line of the swim, among a horde of people in black wetsuits. A mist of the morning shrouded the water. I could see the slight chop on the surface, as the wind pressed on the dark lake.

I hardly slept an hour the night before the Ironman, not due to nerves, but because my old college roommate, who offered to stay with me at the hotel for moral support, had snored the entire night. Fatigue already had a hold of me and I hadn’t yet started the race that would take the entire day.

The size of the crowd of triathletes surprised me, as there were so many people willing to partake in the same challenge. The swimmers lined up by ability, so I move to the back of the pack, knowing that I would not impede those who actually knew how to swim. The line crept forward as the race started. To reach the water it took nearly forty minutes as only a few people entered every few seconds, staggering the swimmers to minimize the inevitable collisions that happen in the water. The sun peeked over the horizon.

Suddenly I was in the water and stroking at the water with my head down, breathing from side to side every three strokes as I had practiced. The lack of sleep I could feel in my arms and legs, the muscles and tendons felt acidic and brittle. But that was a secondary concern as the waves exceeded my ability. The chop in the water slapped at my face whenever I turned into a wave and I began swallowing water and sputtering, gagging and nearly choking several times. My training had been done in placid pools and lakes, not ocean-like conditions. Only once or twice on a vacation had I swam in the surf and I lasted only a short time where the waves were breaking. Other swimmers ran into me and I ran into them and control of the day quickly slipped away from me.

I panicked. Within two minutes I felt spent. Earlier that year I recalled reading about several drownings at races. I wanted to get out of the water as fear of drowning reached up from the bottom of the lake like seaweed on my feet. But I could not tuck tail and run now, not after all the training, not after telling people about my goal. The reason why those people had drowned flashed through my mind as I thought about my intention to continue. Had they experienced a moment where they should have stopped, where their instinct had warned them?

I bobbed in the waves for a bit and then swam forward. Again the waves struck my open mouth when I turned for air and I swallowed a mouthful, again gagging and nearly vomiting. From the pool I had learned how to take a mouthful and keep going, since that is part of swimming (and the joke is to think of it as hydration). Getting water in the belly wouldn’t kill me. But getting water in my lungs would kill me and the amount I seemed to be taking in worried me. A frantic desperation came over me as I thrashed against the water, kicking and pulling, kicking and pulling, fighting the entire lake, like Achilles fighting the river God, Scamandros, in the Iliad. “And in his confusion a dangerous wave rose up and beat against his shield.” Except Achilles survived that fight with the help of Athena, who was definitely not coming to my aid in this wine-dark lake. The fatigue and fear struck me hard and I swam over to a kayak that floated near the swim course.

The man in the kayak, my version of Athena, was a mortal spotter for swimmers in need of help. I asked him if I could put my hand on his kayak for a moment to gather myself, and he nodded and said, “Just don’t pull too hard or we’ll both be in trouble.”

For thirty seconds I gently held onto this little life raft, collecting myself and watching the chaos around me. From there I could see swimmers running into one another. Swimmers turned up like a pod of belugas catching mouthfuls of air. The colorful swim caps dipped under and re-appeared. The sound of continual splashing and thrashing filled the air along with the slap of the waves against the bodies. I told myself to relax, remembering that water cannot be controlled or defeated. To let myself float and flow with the water would spare my strength and allow me to rudder myself toward the first buoy. Watching the swimmers and the directions of the waves I suddenly realized why I was drinking so much water. The slap of the waves came from the left, therefore I needed to breath on the right.

Upon resuming I stopped kicking and dragged my legs behind me, letting them float like logs. The water lifted and dropped me on the waves. No longer fighting it, I pulled myself through the water and breathed every fourth stroke, on the correct side, where no waves could surprise my face. In true amateur form I swam way off course several times, being way off track and not aligned with the buoy. The rookies like me formed an enormous gaggle in the water, spread wide in all directions, clueless to direction. But I didn’t let it discourage me and I swam back to the thrashing flock to get in line, only to get off course again minutes later.

At least once a minute I ran into another person, or someone ran into me. Typically we would both stop and say “Sorry,” and then continue on. I suspect among the elite swimmers there is a less forgiving spirit, but in the back of the pack most people seemed to understand that mistakes happened…a lot.

When I passed the first buoy I felt like my body had called up some reserve energy forces, most likely summoned by the adrenaline and fear felt in the first few minutes. I had done 2.4 miles in the pool a few times so I knew I could slog this out, and “Just keep swimming” like Dori, the fish in Finding Nemo. An old shoulder injury tended to come back when I swam and I felt the joint crunching with each stroke, but I kept throwing out that arm, over the top, over the top, until I came to the next inflatable buoy, which I ran into with my head. I laughed at my navigational skills and continued onward, zig-zagging through the lake.

Turning at the last buoy a sense of elation came over me. Exhaustion neared in my arms from pulling and pushing. But with merely a third of a mile to go I knew that this milestone in endurance would be met and passed. The shore neared, slowly, as I kept peeking up every few strokes. Some kayakers and paddle boarders shouted encouragement. When I reached the shore I lifted myself out of the water and a sense of joy struck me. The “peelers” told me to lay down and they stripped off the wetsuit, and I ran, nearly naked, through a gauntlet of people to the transition area, smiling the entire way, ready to get on the bike and continue on.

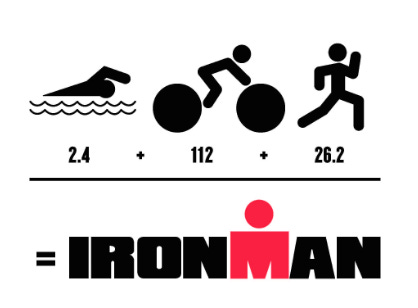

After the swim, the bike ride seemed almost peaceful as much of the ride was a cruise through country roads. I had upgraded my Wal-Mart bike to something better, though still going cheap compared to many of my fellow riders. The 112 mile bike ride is the fun part because of the scenery and speed. The only worrisome part of the ride is descents of steep hills, where I watched my speedometer hit 45 miles per hour. On skinny road bike tires, one slip or over-correction in steering can lead to an ambulance ride. With cycling, I tend to find that another mile can always be “gutted” out, or achieved by grit alone.

The marathon at the end marks the beginning of the pain. As I mentioned that in a normal marathon, the race starts at mile 20. In a full Ironman, this is still true, but the pain arrives around mile 13. Or sooner. The first half of the marathon felt like a joyful hurt as I exceeded my target pace, only to find that my steps began to feel like hurdles in the second half. A kind person tipped me off before the race to find the chicken broth in the late hours for a restoration of the body. He said, “The chicken broth has pulled many triathletes back from dark places where they wanted to quit.”

To my amazement, people lined much of the race, yelling encouragement, drinking and partying while we passed by, giving us a laugh or a reason to smile. The event is inspiring to others and I realized that selfishness in the pursuit does have something to do with it, but at the same time these events, while useless, can inspire and bring joy to this world.

Rain started to fall in the last hour of my race and my shoes squirted water out the sides with each step. Several times I had to walk to allow the pain to settle out of the muscles and to let a cramp fade away, but I resumed as soon as possible. My wife appeared on the side of the road, supporting me, giving me hope. My best friend in the whole world, always, through the years, through my drinking, my arrest, my recovery, my moodiness, and my searching. And I am embarrassed to know that I have forgotten from time to time to put our marriage into its proper placement in the order of priority.

As I came toward the finish line and crossed under the large digital timer, onto the red carpet, I heard the iconic saying, “You are an Ironman” coming from the announcer, Mike Reilly. The mission was complete. I now had over three years of sobriety under my belt, a multitude of marathons for proof of change, and now the label of Ironman to boot. I had proven I could change my life. Real change, not just temporary modifications. The emotions came up again, not as strongly as the first marathon that I completed, but the fleeting contentment of accomplishment landed on me for a while. Another goal crossed off the list of things to do, with adversity faced and overcame, where I might have tapped out in the lake earlier in the day I continued, to the end, into the rainy night. I had everything in life and now proof that I could set and accomplish just about any goal. I fell asleep that night wearing my “Finisher” t-shirt and woke up feeling semi-normal, not nearly as sore as I expected. A new day in the post-race glow began and I posted this victory over self to Facebook, and I felt the power of the Likes gathering in me, as my friends and acquaintances online commented and validated my pursuit as worthy.

For a few days I basked in that glory of achievement. Who am I kidding, I still think of that day as a highlight because the experience was unique and powerful to me. But within a week I started inspecting my bike and shopping for new shoes. I started looking up race schedules, to find the next challenge. After a week, the euphoria faded and flat-lined, and once again I was wondering:

Now what?